Fight for solar rights sparks deeper look at electric cooperative

Electric cooperatives hold a lot of promise for solar supporters. Cooperatives don’t have customers. They have member-owners. This structure is supposed to make them responsive to people they serve. Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case.

Our recent look at Michigan’s Upper Peninsula found that solar is booming in the area, but was running up against utility-created roadblocks. The Upper Peninsula is served by a patchwork of investor-owned utilities and rural electric cooperatives. One cooperative in particular, the Ontonagon County Rural Electrification Association (OREA), shows how electric cooperatives can block our solar rights as well as fall far short of the transparency and customer responsiveness they were designed to have.

OREA serves about 5,000 member-owners across the Upper Peninsula. It is the state’s smallest electric cooperative. In 2015, it announced it would no longer compensate its member-owners who had solar at the net metering rate. It cut the compensation rate to the electricity’s wholesale rate. This cut the metering credit by about 10¢/kWh. This decision led to an outcry in the community.

“There were people with stacks of panels in their yard waiting for install, told they wouldn’t be able to install,” said Sarah Green an OREA member-owner and solar homeowner. “The complaints caused the board to change their decision.”

Green and other solar supporters in the area were successful in getting the cooperative to back off from undercompensating its member-owners with solar. In the meantime, the cooperative said it would pay for an outside consulting firm to perform a cost of service study. The purpose of the study is to determine how the utility should value solar energy.

The attention caused by the board’s decision trained a closer look on some of its other practices. Member-owners found several irregularities in the way the OREA board operates. They found issues with the board elections and with compensation.

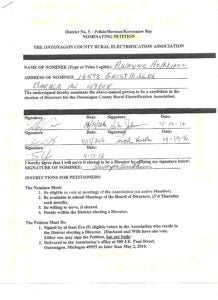

Member-owners determine who serves on the OREA board by vote. Seven board members serve offsetting three-year terms. Candidates for board must submit a nominating petition that includes the signature of five OREA members, including the signers’ address. A review of the nominating petitions for several elected board candidates in 2016 found that their petitions did not include the signers’ address.

Petitions were deficient in other ways as well. Names on one petition were filled out so illegibly, the candidate could not identify who the signers were. OREA by-laws stipulate the petitions must be returned by the first Monday in May. Several petitions had no marking of when they were submitted to the OREA office for approval.

An additional sticking point in the community is the way the board is compensated. OREA by-laws say that board members cannot receive compensation for serving on the board. OREA by-laws do allow the board to pass a resolution granting board members remuneration for their participation in board meetings.

Currently, each board member receives $325 for attending each of the board’s monthly board meetings, or $3,900 per year for 12 meetings. OREA member-owners have been unable to get the resolution board members passed that allowed these payments to be made.

Documents from OREA show that board members were paid even more than that. In 2015, the last full year we have records, the seven board members were paid a combined total of $33,780. The board chair was paid a total of $8,575.

“Let me see the original resolution to give you this compensation,” said Mel Haskell, an OREA member-owner who has been active watchdogging the board. “They are not legally required to show [members the resolution].” But, he notes: “They’re not prohibited. They could do it if they wanted to.”

These issues came to a head at last year’s annual member meeting. Member-owners unhappy with the board’s actions showed up in droves. They were able to get several resolutions passed to make the board more open and responsive to member-owners. This included a resolution to implement a redistricting of the board seats. Two of the seven board seats were significantly larger than the other five. This disenfranchised member-owners who live in those districts.

It remains to be seen if this increase in public pressure will bring more accountability to the board. “They could support community solar, wind etc.,” Green said. “They don’t because they’re extremely backwards looking.”